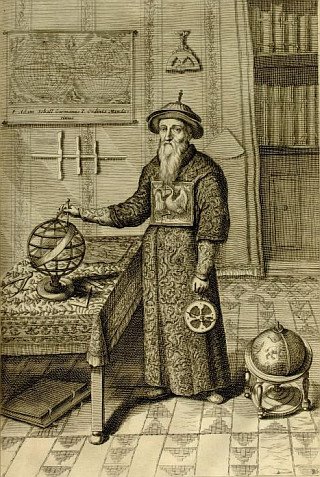

Like a mouse in the pantry, I kept on a shelf in a dark corner at the back of my uncle's bookshop a collection of treasures. These were baubles, bits of glass, pinecone people with acorn heads, etchings and plates come loose from their bindings, and books liberated from the tables where they were to be sacrificed to commerce. I imagined no one knew of my mousehole, hidden as it was where two giant cabinets met at an angle, and reachable only by a dusty person of diminutive size, but I now think it was a luxury granted me by the compassion of a man toward an orphan with an appetite for knowledge. The largest (and most valuable, had I been sensible of such things) was a book of marvels by "the most miraculous mystagogue of nature": China monumentis, qua sacris quà profanis, nec non variis naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, by Athanasius Kircher. This musty folio edition, published sixty years earlier, and based on the tales of jesuit missionaries and envoys, embellished and elaborated in Kircher's fertile imagination, introduced me to the wonders of the Great Wall, to the pine-apple, to Confucius Trismegistus(!), to the use of pictographs as a method of writing, to tea and silk, geomancy and flying turtles. I travelled across those tall Thibetan peaks many times in my imagination, and studied those complex characters until my eyes crossed in hope of deciphering their meaning.

Like a mouse in the pantry, I kept on a shelf in a dark corner at the back of my uncle's bookshop a collection of treasures. These were baubles, bits of glass, pinecone people with acorn heads, etchings and plates come loose from their bindings, and books liberated from the tables where they were to be sacrificed to commerce. I imagined no one knew of my mousehole, hidden as it was where two giant cabinets met at an angle, and reachable only by a dusty person of diminutive size, but I now think it was a luxury granted me by the compassion of a man toward an orphan with an appetite for knowledge. The largest (and most valuable, had I been sensible of such things) was a book of marvels by "the most miraculous mystagogue of nature": China monumentis, qua sacris quà profanis, nec non variis naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, by Athanasius Kircher. This musty folio edition, published sixty years earlier, and based on the tales of jesuit missionaries and envoys, embellished and elaborated in Kircher's fertile imagination, introduced me to the wonders of the Great Wall, to the pine-apple, to Confucius Trismegistus(!), to the use of pictographs as a method of writing, to tea and silk, geomancy and flying turtles. I travelled across those tall Thibetan peaks many times in my imagination, and studied those complex characters until my eyes crossed in hope of deciphering their meaning.It was therefore no accident that when in 1743 I was in dire need to flee as far as I could from my infernal husband I arranged passage on the Swedish East Indiaman “Götheborg" to Canton, and there stole ashore. For two years I journeyed in a country more wonderful than Kircher ever imagined. I have since returned to China many times, and long since learned to speak the language of the Mandarins, and read their classics, and contemplate the lessons and histories of their many scholars.

On All Saint's Day I return to China, once again by way of Canton, whence I travel northward to Shanghai and Beijing, for a fortnight and a week. I remain silent on the nature of my business only because it must gestate to term before being brought into public light, but I shall report on my progress where chance and opportunity allow. You will discover I am not fond of the moral condition into which business in China has descended (and which recalls to me the France of patronage and privilege of the Ancien Régime), nor the profligate waste and arrogance of the newly wealthy, no less than the importunity and knavery of the poor, but I remember it is a beleaguered population much confused and misguided by inconstant policy and ill used in the past. Great change is borne only with great suffering, and the material improvements that have been wrought at so enormous a scale and for the benefit of so many is no less wonderful than the Imperial glory long since vanished.

1 comment:

I think it's easily forgotten by those of us in our comfortable chairs in our nice, little towns, but the change that occured to catapult China from its ages-old darkness to its present state of metamophosis should be considered a Wonder of Humankind. Such an immense undertaking - even had it failed - hints at powers in humanity that have never before been seen. And it succeeded - and goes on - quite extraordinary.

Post a Comment